By Joshua Taylor

This year’s Anzac Day once again provoked frenzied and hyperbolic commentary about the nation’s collective identity from across the political spectrum.

In the absence of another (brown) straw-(wo)man to excoriate for exercising their freedom to articulate divergent perspectives and challenge nationalist orthodoxy through simple truth-telling, this year’s highlight was certainly Karl Stefanovic working himself into a flap about a superhero movie opening to great fanfare on such a sacrosanct day. This particular episode of concocted outrage lacked the intense vitriol of last year’s Abdel-Magied saga – Prue MacSween hasn’t threatened to run anyone over… yet – but it is another demonstration of the immense power and weight attributed to Anzac Day, and the prominent role it has assumed in the formation of our imagined identity.

The competing discourses surrounding Anzac Day are significant less so for their commemoration of the unnecessary and tragic deaths of over 8,000 young Australian men, under a British flag in the invasion of a foreign state, than for their attempt to demarcate the ideological boundaries of Australian identity. In the same breath as they insist that such a day should never be ‘politicised’, politicians and commentators simultaneously enact a rehearsed nationalistic narrative increasingly focussed on militarisation, a narrative itself born of a particular reading of history steeped in the legacy of our colonial origins. Their instinctive and immediate move to quell and rebuke any criticism of the culture, mythology and indeed politics surrounding the day presents in itself an opportunity to lay bare one’s fair dinkum credentials as a true-blue Australian. Failure to do so would represent treasonous acquiescence (another instance of the silent conformity demanded by nationalist hardliners). It’s a certain brand of jingoistic hysteria that the historian Geoffrey Serle presciently termed ‘Anzackery’ in a Meanjin essay back in 1967 (insightfully explicated in contemporary times by columnist Paul Daley).

The hypocrisy of the virtuous defence of Anzac Day’s solemnity, lest it be tainted by the brush of ideology, is reflected in the current debate over the $500m expansion of the Australian War Memorial. The Memorial’s current director, former Liberal Party leader Brendan Nelson, refuses to extend the institution’s purview to include the Frontier Wars of colonisation, yet is advocating for the commemoration of Operation Sovereign Borders.

On the one hand, the push for the recognition and appropriate commemoration of the Frontier Wars has strengthened in recent years. To legitimise the violence instigated by colonisation, and Indigenous people’s resistance to this violence, as historical fact would be a powerful instance of truth-telling that would disrupt lingering sentiments of terra nullius and contribute to meaningful reconciliation of our national traumas. It is derided, however, by those who refute what they consider a ‘revisionist’ history motivated by political correctness and virtue signalling, and who feel their stake in the national narrative would by impinged by its enlargement.

On the other hand, Nelson is pushing for the institutional memorialisation of a highly contentious – both morally and legally – policy of a current government. Operation Sovereign Borders does not relate to Australian involvement in a theatre of conflict, but to the (illegal) implementation of asylum seeker boat turnbacks. It’s an outcome of Tony Abbott’s successful 2013 election campaign, pledging to “stop the boats” – itself a policy position geared to appeal to a disenfranchised electorate through reactionary populism. Commemorating it as part of the Memorial would take an active policy out of the realm of public debate and embed it within our national mythology.

The Memorial’s response to both issues reflects its role in shaping the national narrative. The dismissal of the Frontier Wars’ as unworthy of a place in the Memorial is a carefully considered position, one designed to appease popular sentiment and keep intact our current politics of remembrance. The possibility of commemorating Operation Sovereign Borders alongside the conflicts of Gallipoli, Villers-Bretonneux and Kokoda is equally mired in a political worldview. What this comparison demonstrates is that national narratives are never stable or untouchable. They are dynamic, always shifting, deeply connected to ideology and politics, constantly revised and re-enacted. The commemoration of Anzac Day, which has assumed such a profound space in the national consciousness, and the conflicting discourses it generates are no different – from blind Anzackery to provocative arguments for the recognition of the Frontier Wars. As with every aspect of our national identity, it should be – needs to be – open to contemplation, critique and change.

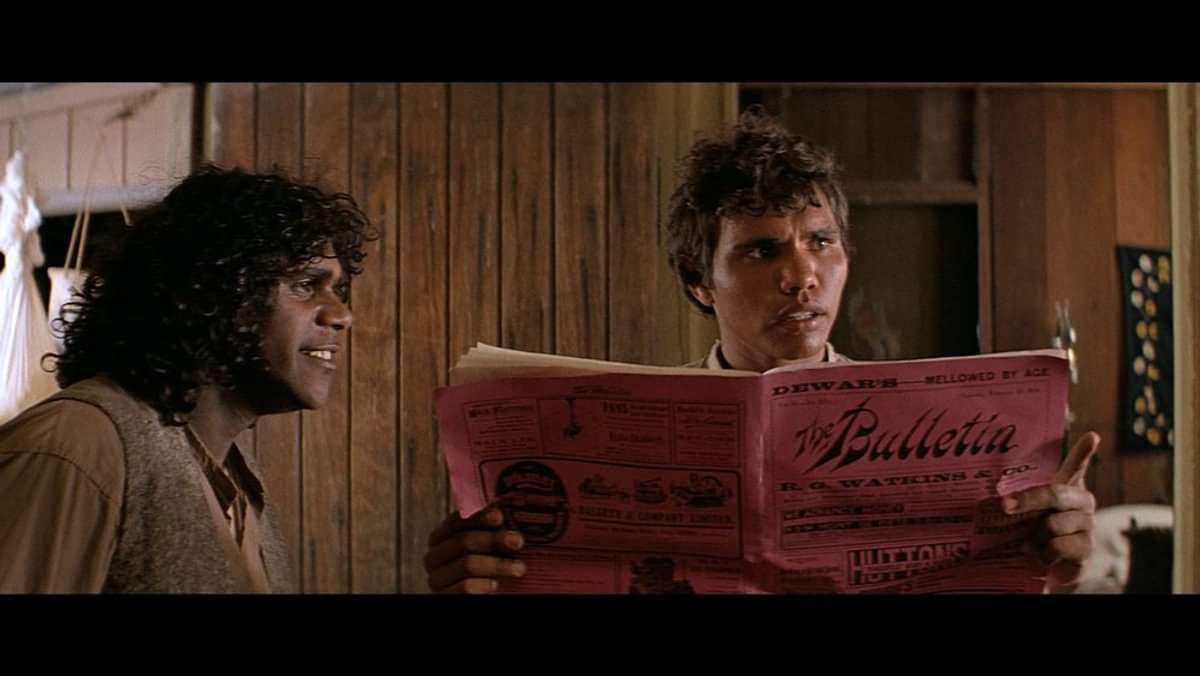

It is against this contemporary backdrop that The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith (Fred Schepisi, 1978) offers us a profound reimagining of the politics of race and national identity on the Australian Frontier. Adapted from the novel by Thomas Keneally (1972), itself inspired by notorious murderer Jimmy Governor, it’s a challenging confrontation to the civilities and sensibilities that underpin discourses of race relations, both at the time of its release and now. But from our standpoint, as culture wars continue to rage over who and what are worthy of shaping the national narrative, what strikes me most is the film’s radical inversion of the politics of violence, refuting the presumption of Indigenous passivity throughout colonisation through the language of colonialism itself.

On the cusp of Australian Federation, Jimmie Blacksmith is raised into adulthood by Reverend Nile and his wife, who share hopes of civilising a ‘half-caste’ Aboriginal. With a reference from his respectable foster parents, Jimmie sets out into the world in search of work, negotiating a hazardous liminal space between blackness and whiteness. His genteel upbringing permits him to find work other blackfellas can’t, but he’s repeatedly taken advantage of by his white employers. At his first job, fence-building for a farmer, the boss unfairly nit-picks his work as an excuse to dock his pay, then refuses to write him a reference when the job is complete (to hide his own illiteracy). Jimmie’s next job is working for the local constable, who spitefully deploys him against other Aboriginals. He witnesses constant racist cruelty, and is then implicated in the cover up of the murder of an Aboriginal in the constable’s custody. Jimmie nonetheless holds onto his ambition for integration into white society. He finds stable work on the Newby family’s farm, and he begins to court Gilda, a white woman. When she falls pregnant, Jimmie does the virtuous thing and marries her, building them a small hut on the property and dutifully taking care of her – even after the embarrassing revelation when the baby is born bearing none of his colour. He still clutches onto the social aspiration and family values he learnt from the Reverend.

Despite this, the Newby women encourage Gilda to take her child and leave Jimmie, rescuing herself from a life tied a black man. Meanwhile, Jimmie’s brother Mort and his uncle Tabidgi arrive on the property, and Jimmie puts them to work alongside him. Sceptical of Jimmie’s relationship with Gilda since the baby turned out not to be his, Mr Newby uses this as an excuse to deny Jimmie pay and rations. A confrontation turns sour, with Jimmie threatening Mr Newby, who then directs Jimmie and his “tribe” to pack up and leave.

Jimmie decides that he needs to “give these whites a scare.” He puts Tabidgi to the task of asking Mrs Newby for rations, whilst hiding an axe under his jacket. When Mrs Newby threatens him and reaches for a gun, Jimmie runs at her and swings his axe. Mrs Newby drops to the floor whilst her daughters look on in sheer horror. Jimmie chases them around the kitchen as they shriek, cornering them, spraying blood across their pure white dresses, the white tablecloth and white porcelain plates. By the end of Jimmie’s brief episode of rage, four women lay dead.

Jimmie and his companions take to the bush, pursued by a band of men on horseback. Tabidgi, Gilda and the baby are left behind with Jimmie and Mort continuing on. Here the narrative draws on the now-familiar trope of the Indigenous outlaw chased by the authorities, drawing on their knowledge and deeply spiritual association with the land to outwit the whitefellas in pursuit, who are out of their depth in a foreign and hostile landscape. It a generic hallmark of Australian cinema most recently reincarnated in Warwick Thornton’s brilliant neo-western Sweet Country (2017).

Jimmie and Mort return to the farm of Jimmie’s first employer, where they murder not only him but his wife and baby as well. After they wound a schoolteacher and take him hostage, they argue about the morality of Jimmie’s wave of vengeance, the reluctant Mort troubled by their slaying of women and children. The schoolteacher expresses sympathy for Jimmie’s anger in response to the violence, disease and alcohol colonisation brought; from this common ground, he convinces Jimmie to go on alone so that Mort, an accidental accomplice more than murderer, might have a chance. Shortly after, Mort is found, shot and killed.

Jimmie narrowly avoids a similar fate, tending to his wounds in the bush. Delirious and all but defeated, he seeks refuge in a convent, where he’s discovered sleeping by an unsuspecting nun. The police struggle to keep the men from pulverising Jimmie to death as they take him into their custody. The film closes with Reverend Nile reading Jimmie his last rites in his cell, as the onlooking hangman provides assurances that, despite Jimmie’s uncharacteristic physical features, the hanging should proceed without any problems.

The film offers much by way of its affront to the civilities of the debate around race relations in Australia. In the absence of a pronounced ethical and political angle, it presents us with conflicts, contradictions and complexities. It seems to force a white audience to weigh the moral perversions of racism and murder against each other. In the process, Jimmie’s flawed character undermines essentialised representations of Aboriginality. The sympathy we’re expected to extend to Indigenous ‘victims’ of colonial racism and aggression is subverted by Jimmie’s shockingly gruesome acts, completely disrupting the condescending presumption of Indigenous passivity in response to white settlement.

Does Jimmie’s explosion of violence revert his character to a white vision of the noble savage, beyond the reach of civility? Or is Jimmie’s outburst, whilst never morally justified, a humanising episode of rage, the only possible response to such torment from someone who can simply take no more? It’s an ambiguity that imbues the film with immense power, a complexity that echoes the character of Marbuck in Jedda (1955) – Australia’s first colour feature and first film starring Indigenous lead actors – who has been read equally as a violent kidnapper, a demeaning personification of the imagined noble savage, or as an Indigenous rebel, the anti-hero resisting the encroachment of white settlement.

Early in the film, the subject of the Boer War is debated amongst the settlers, considering the merits of England’s declaration of war and the necessity of Australia’s involvement. Jimmie enquires, “‘Declared war.’ What does that mean, boss?” He gets two answers. Firstly, “England has been left with no alternative. They hope that military might will prevail where common sense fails.” Then, “It means they can officially go in and shoot the bastards.” These responses foreshadow the film’s most politically-charged moment, just after Jimmie’s murderous spree has begun. He announces, “I’ve declared war. That’s what I’ve done. I’ve declared war!” Schepisi cuts to a low angle long-shot landscape, looking up at Jimmie on the top of the ridgeline, as that last word echoes through the valley.At this moment, Jimmie has reframed the violence of the colonial frontier through the language and logic of colonialism itself. Perhaps it is because Jimmie is partly a product of a white environment that he sees the power of such a declaration – in the inversion of the power dynamic between coloniser and colonised.

Not only does his declaration powerfully disrupt any lingering notion of Indigenous passivity, it provokes reflection on the legitimacy of violence on the frontier. Does a declaration of war, as the English declared on the Boers, make a conflict worthy of our attention? Does it bestow it a level of authority and legality that earns it a place in our national history? A place on the walls of the Australian War Memorial? A place in the formation of our collective identity?

The Boer War is commemorated by the Australian War Memorial, whilst the Frontier Wars are not. Wars of the federated nation are afforded not only recognition in our collective history, but an active, predominant role in the shaping of our collective identity, whilst the violence involved in establishing that federation is ignored. The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith, in radical and provocative gestures, profoundly connects to our contemporary conversations about Australia’s history and identity. It blows apart the myths of a militarised identity, making space instead for the recognition of colonial violence on our own land. It’s an unforgettable film in many ways, but at this present moment it feels prescient for reminding us of our true history, in all of its complexity and ambiguity – of who else’s blood was spilled as our nation came of age.