By Joshua Taylor

For an Australian work of a popular art form to dare to interrogate the darker corners of our collective identity is an ambitious task. To take on the great weight of nationalist mythology in the attempt to dissect its dangerous undercurrents, overcoming a pervasive fear of projecting pretension and condescension, is courageous.

Representations of ourselves that inevitably shape a perspective on the nebulous concept of Australian identity, still frail from its failure to reconcile the traumas of colonisation, have long suffered from the well-documented inferiority complex of the ‘cultural cringe’. To paint or write or perform any attempt to embody a kind of quintessential Australian character still induces fears of provincialism and parochialism – especially when the intended outcome is one of profundity.

Yet the ordinary punter, as much as the politician, is constantly appealing to the ideals of Australian-ness: a laidback demeanour, the fair go, passing the pub test, and that ultimate aspiration and precise gauge of virtue, being a ‘good bloke’. Our sense of a national ethos still carries weight. To critique this character is to challenge the sacrosanct.

Such sanctity warrants scrutiny. Against our instincts to avoid self-centredness and maintain a relaxed indifference, it is important to examine our own conception of ourselves, and in particular to be honest about its failings.

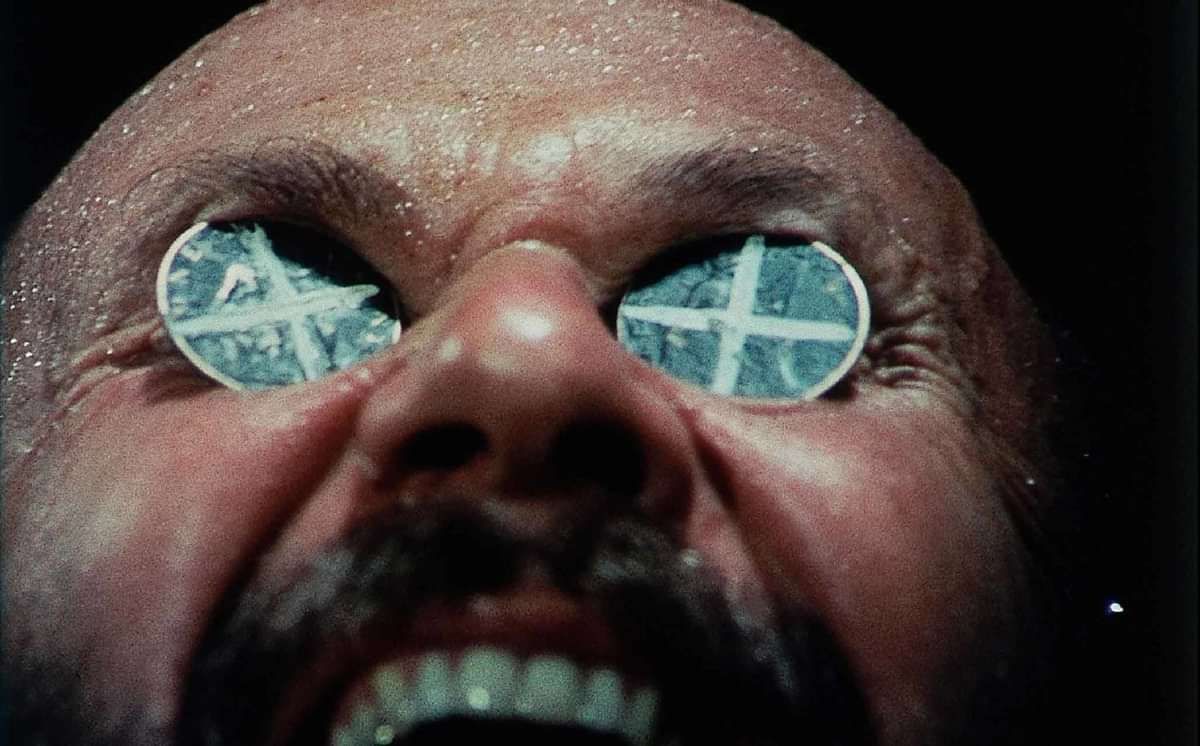

Ted Kotcheff’s Wake in Fright (1971), a searing outback classic with a smouldering density of psychological thrills, confronts us with these stories that we tell ourselves about ourselves and the virtues we seek to admire. It offers a coalescence of the national myths that have been elevated to the point of patriotic adoration – the hostile outback landscape, the isolated rural town, the sacred ANZAC legend, absolute devotion to mateship and a rambunctious obsession with alcohol. But here, such myths are projected as a sinister hallucination, beneath which lies the paradoxical madness of being trapped in the most expansive and limitless of places. It’s a revelation that unravels the enigmatic psychic constitution of the collectively imagined Australian male – the very originator and gatekeeper of this a self-perpetuating mythology.

John Grant, an English schoolteacher posted by the Education Board to the remote outpost of Tiboonda, sets out on his summer holiday to Sydney, a beachside idyll to escape the heat and dust of the outback and rekindle a romance. He must endure one more night in the mining town of Bundanyabba – “The Yabba” – as he waits for his flight, before his emancipation by surf and sand.

Straying into the local pub for a drink, John begins a series of encounters with increasingly peculiar characters and eccentric pastimes, the experience of each oddity soaked in more and more beer as the film wears on. The unnervingly friendly policemen John meets in the pub takes him to a favourite local haunt for a steak, where he witnesses a secret and intensely serious game of two-up – “A nice simple minded game,” sneers the arrogant Englishman. Seduced by the excitement of the jeering and jostling men, he makes a few bets with success. A few spins later and he is penniless. His dash to the coast is thwarted.

With no money and nowhere else to go, John returns to the pub the next day where he is wooed by a relentless man named Tim Hynes, both hospitable and authoritative – “Have a drink, mate.” John joins Tim and a cast of boisterous blokes, Dick, Joe and the strangely philosophical Doc Tydon, as they tear their way through a wild bender followed by a gruesome and gratuitous kangaroo hunt. His mind hazy under the influence, John is torn between his immediate revulsion at the men’s violent and brutish larrikinism, and his desire to prove he too is one of them. Moments later and he is wrestling a kangaroo, clumsily stabbing it to death in imitation of his companions.

Back in Doc’s cabin, he and John keep drinking and clowning until the buffoonery turns sexual. The next morning, John stumbles down the high street of The Yabba, covered in dirt and sweat and self-loathing, rifle in hand, a memento from the hunt gifted by the Boys. He finds his suitcases, all packed for his holiday, in the pub where he’d left them. He hitchhikes to Silverton, where he sources a ride from a truck driver going through to the city. Relieved to finally have a way out of the desolate outback, John speaks with an almost calm resignation when the truckie wakes him not to the azure blue of Sydney Harbour, but the dusty wide streets of The Yabba.

“You know, I thought you said you were going to Sydney.”

“You said city mate. Bundanyabba’s a city, ain’t it?”

John’s brief stoicism quickly caves in to his psychological fragility. Determined to exact revenge on the man who broke him, he rushes towards Doc’s cabin. It’s empty, but he waits, just long enough to turn the rifle on himself. John somehow survives, and wakes in hospital to the policemen softly cajoling him to agree it was an accident (there’s no room in The Yabba for a conversation about the grim reality of frequent rural suicides). His holidays ended, he returns to Tiboonda to resume his teaching post. Where the film opened with a slow aerial pan of the vast, barren red plains, equally mesmerising and menacing, it closes on the same image, this time slowly ascending over the train tracks that cut the landscape in two: the only way in and the only way out.

Wake in Fright’s brutal reading of our national psyche avoids condescension through its remarkably affective aesthetic. The camera is measured and assured, a understated presence that belies the bubbling intensity of John’s tragic descent into madness, and heightens the sporadic, truly frightening montages materialising his psychosis. It’s a bold and innovative style typical of the confidence and vigour of 1970s cinema that holds its own against any of the canonised classics of the European New Waves and New Hollywood.

It is also notable for its cult mystique as a ‘lost’ film. The story goes that following a poor reception by local audiences, disgruntled with such an ugly depiction of Australian life, the film had little circulation after its release. By the late 1990s, the only existing 16mm and 35mm prints were in extremely poor condition, whilst the original negatives were nowhere to be found. The film’s editor Anthony Buckley began a long search, and the negatives eventually turned up in an archive in Pittsburgh, in a crate marked for destruction. The National Film and Sound Archive of Australia began a restoration project in 2004; in 2009 the film was rereleased, and played at Cannes as a restored classic, the festival where it had premiered nearly four decades earlier.

Perhaps it is not surprising that it took an outsider like Kotcheff, a Canadian, to successfully navigate the precarious task of representing nationalistic tropes without descending into triviality, like so much of the shallow Australiana produced for foreign audiences. On the contrary, Wake in Fright’s critique could hardly be more ambitious or scathing. It materialises to disturbing excess the mythologies that obsess our collective imagination of who and what we are.

These are stories with which we are intimately familiar, but which we attribute to an Australia of the past, or at least an Australia that only survives in rural outposts. For someone of my generation, to see peculiar and now antiquated practices such as two-up and roo shooting for sport performed with such fervour and sincerity is revelatory as a social realist document as much as it is for the unflinching social critique that the film is carefully drafting.

As an aside, it is worth noting that the sickening images of wounded and convulsing kangaroos are real. The filmmakers (including Kotcheff, a vegan) accompanied a group of licensed shooters on a hunt one night, taking the actuality footage that would be interspersed with close-ups of the actors manically firing their rifles. The gore of the scene that unfolded before the filmmakers was testing, but it was the hunters’ delight in the carnage that really troubled them. As the night wore on, the hunters drank more and more whiskey. They started to miss, and kangaroos were hobbling around with intestines trailing behind them. The crew orchestrated a power failure to put an end to the gratuitous violence. There’s an uncanny correlation between the hyper-masculine, drunken violence of the hunt in the film and the actual hunt from which it takes its shocking images; a blurring of art and life that extends beyond the documentary footage.

However, to depict roo shooting and two-up games hardly makes Wake in Fright anachronistic. Rather, the film interrogates with immense courage the great mystery of the Australian male. It scrutinises their cultural ideology of mateship, bonds forged through beers and yarns, which still holds currency today as that most unique and vital trait distinguishing the Australian disposition. Men, mateship… and the raft of concomitant pleasures and follies, both innocent and violent, that go along with them.

After John’s arrival in The Yabba, a taxi driver regrets that he might only stay for one night, since it’s “the best place in Australia.” When John asks why, he replies, “It’s a friendly place. Nobody worries who you are, or where you come from. You’re a good bloke you’re alright.”

A good bloke. Despite anything else, this is what counts.

There’s a paradox driving mateship. “Have a drink, mate” – a gesture of openness, an invitation to enter sanctioned male spaces, to participate in heavily coded male behaviour. But simultaneously, as the “first commandment” of a culture of “aggressive hospitality” and “virile togetherness,” as described in the Preface to the film’s script. The phallocracy that prides itself on an almost radical egalitarianism is similarly defined by a dangerous homogeneity, an obsession with fickle virtues of character that avoid description in conspicuous detail but nonetheless prescribe the terms on which men interact and deem each other worthy.

The men of Wake in Fright make a point of welcoming John into their circle, and yet take a position of righteous indignation at any hesitation to have a drink, make a bet, throw a punch, even slaughter an animal. And so we encounter the darker currents running beneath our collective ethos: the oxymoronic duplicity of aggressive hospitality, the unshakable bonds of mateship entirely conditional on social uniformity. As much as Wake in Fright immerses us in the heat, dust and sweat of outback life, it is this explication of the Australian (male) disposition, in an environment without purpose or escape, that is its most profound and enduring offering.